Jerry Momoda may not be a name that many modern Tekken fans are familiar with, but the former Namco US product manager played a huge part in launching the iconic fighting game in North America.

Momoda originally arrived at Namco in 1993, after holding market research and product management roles at companies like Nintendo, Sega, and Atari Games, and almost immediately began pitching Namco of Japan on the importance of getting into the fighting game genre. This was based on seeing the success of games like Mortal Kombat and Street Fighter II in the arcades. Then, later, once work on Tekken had actually begun, he assisted the Japanese team with helping get the game ready for the US market, eventually going on to perform the same role on the next two Tekken games before departing the company in 1998.

A couple of weeks ago, we were lucky enough to get the chance to sit down on a call with Momoda to chat about his involvement with Tekken, ahead of the series's 30th anniversary later this year. Momoda was happy to go over his career at Namco with us, answering all of our most pressing questions. Some of the standout moments include his memories of pitching a fighting game to Namco chairman Masaya Nakamura, his explanation for why he hated the name Tekken, and his reflections on the decline of the coin-op market. You can read our interview below:

Time Extension: To start, it would be great to know, how did you get the job at Namco in the first place? And what was the North American setup like when you joined?

Momoda: I was approached while I was a product manager at Atari Games. There were a couple of Namco employees – Kevin Hayes and Frank Cosentino – who worked at Atari and then left to start up the US Namco office. Before then, Namco always had a presence in the US but didn’t always have a US office. Like when Pac-Man came out, they were licensing their games to Midway. Then Midway put it in a cabinet and did the sales and marketing. The Namco name and legal markings are in the game, but the casual player wouldn’t notice it.

Even at Atari, where I was a product manager, at that time, Namco owned Atari. So I would work on releasing Namco games for the US market. Atari handled the sales and marketing. I enjoyed that work having worked previously with Japanese companies – Nintendo, Sega, and SNK for a while. I was familiar with the process of localizing games for the US market.

Frank approached me about the product manager position. It was good timing because I was growing frustrated with Atari. Their games were becoming less relevant to the US market and a lot of the teams didn’t want to work on games that were more relevant to players. Like fighting games. Even the hardware that Atari was making – their 3D hardware – it was expensive and it wasn’t as advanced as Sega’s and Namco’s.

Time Extension: Where was Namco located back when you were first working there?

Momoda: We were in Silicon Valley. In San Jose, not far from San Jose airport. It was a small office shared with Namco Hometek. We had a warehouse out back. I would be shipped games at different stages of development for review and testing. Local contractors would build our games and assemble kit games. At that time, kits were coming onto the scene. We could make kits and ship them out of San Jose. We had some operations staff there for the Aladdin’s Castles arcades that were primarily in the Midwest, some coin-op sales support, marketing, and Hometek (consumer division) staff. Eventually, all arcade sales and route operations moved to Chicago. I had an assistant who helped with testing games, internally and in the field.

Time Extension: You mentioned in your Tekken "Making Of" on your website that shortly after you joined you visited Japan where you pitched the idea of working on a fighting game to Namco. Do you have any interesting anecdotes about that trip?

Momoda: Before joining Namco, I saw one glaring omission in the product mix. There were no fighting games that could even remotely compete with Virtua Fighter and Mortal Kombat.

It was very clear where the market was going. Fighting games were not a passing fad. And it had been a struggle to get Atari engineering to make a fighting game. They were morally opposed to violence in games. During that time it was a hot-button issue. There was a large effort by senators to control the degree of violence shown in games. Game manufacturers were required to display the level of violence in a game. That was the beginning of what is now game ratings and parental controls. In my opinion, Mortal Kombat crossed the line when pulling out spinal cords. Even Namco’s Splatterhouse was over the top.

So anyway, I studied the market data that was available, spoke to fighting game enthusiasts, and spent hours observing players. I wrote a case study listing what I thought were key elements for a fighting game to succeed. That document was eventually forwarded to Japan. It’s summarized on my website, jerrymomoda.com. A week before the 1993 JAMMA show I was invited to go to Japan and discuss this game that I was proposing. That was a shock, but I was really excited too, because it was a tremendous opportunity. At that time, an American office had little if any influence over what games to develop. The standard protocol was Namco would develop games for the world market, then testing would determine suitability for the US market. If they showed enough potential, we would localize and market them.

I recall that meeting vividly. It was intimidating because it was the company’s global annual meeting just prior to the JAMMA show. In attendance were Mr. Masaya Nakamura (Namco chairman), senior executives, sales and R&D staff, and managers from Namco satellite offices around the world.

My report was distributed previously to key decision-makers, so they just asked a few questions. Remember, I was a new hire and on the job only for a few weeks. We left the meeting feeling somewhat confident, but there was no greenlighting of the project yet. On that trip, we attended JAMMA, visited arcades, and toured R&D. The latter being most important. Not just anyone gets a tour of R&D. Over the years, that was my favorite part of visiting Japan. About two weeks after returning to the US, I received a VHS tape showing some very blocky 3D figures against a static 2D background. I was thrilled. Little did I know that this was the beginning of a franchise that would one day celebrate 30 years of existence.

At first, I thought, ‘What is this?’ Once I realized they were showing early 3D development of a human torso, I was ecstatic. They didn’t even include documentation. It’s important to note that 3D technology in games was still then in its infancy. Three-dimensional objects were comprised of polygons, with a serious limitation of how many could be processed and displayed. Though Virtua Fighter was then state of the art, by today’s standards it was crude and blocky.

Time Extension: How important do you think things like Virtua Fighter were on Tekken? I believe Namco hired several Virtua Fighter developers to work on Tekken, including Virtua Fighter’s designer Seiichi Ishii.

Momoda: It was crucial since Mr. Ishii designed both Virtua Fighter and Tekken. I learned that some developers also came from Sega. Tekken had a very tight development schedule of one year, so he didn’t have time to reinvent the wheel. The similarities in the two games weren’t a coincidence. Tekken was also an opportunity for him. I doubt game designers are ever completely satisfied with the end product. Here, Mr. Ishii had the chance to go back and make the game that perhaps time and resources would not earlier allow.

Time Extension: Did you get to meet the director of the original game on your trip to Japan?

Momoda: No, because I’m not sure it was even a project at that time. On that trip, I met a lot of people. I’m interested to know when and why Mr. Ishii left Sega to join Namco.

Since I didn’t speak Japanese, I didn’t have direct communication with Mr. Ishii. I communicated through my counterpart in the Overseas Department, Kohei Teraoka.

Time Extension: I’m wondering – how often did you interact with your overseas counterpart? And how did you communicate at the time?

Momoda: It’s funny that you ask that because obviously technology and communication was pretty archaic back in those days.

The way it worked back then was mostly through fax and phone. I’d start each day with faxes from Kohei. He forwarded info and projects from R&D to me while I was at home sleeping. I’d work on projects during the day and fax off my replies by the end of my day. I’d then call Kohei early in his day to review what I did that day. And often there were urgent projects I needed to complete before leaving for the night. So I regularly worked evenings. Keep in mind there were many games in the schedule, so I was helping with a variety of games at different stages of development. Tekken was just one of them.

Over the years, my visits to R&D increased. We tried to time meetings along with tradeshows since everyone was busy and by the time of tradeshows, teams had achieved their deadlines and had time to meet. It’s important to note, Japanese game companies worked very hard to adhere to development schedules. Changes to design docs would occur only if they didn’t impact the schedule.

Time Extension: Do you remember what the first characters were that you saw? What were the first fully realized characters that you came across?

Momoda: I first saw images of around six characters. I remember Martial Law, because he was a dead ringer to Bruce Lee. I also recall Paul, King, Jack, and Michelle. There were also characters that didn’t make the cut, but I don’t recall enough about them.

I preferred a more edgy look and feel to characters so I didn’t care for the cute female characters. But they added such diversity and depth. I believe their inclusion has aided the game’s longevity.

While the similarities to Virtua Fighter’s characters were obvious, Tekken’s superior four-button control set it apart. I feel it was the stroke of genius that made Tekken superior. What better way to control a fighting game than to have the ability to control each limb?

Time Extension: In terms of your go-to characters, was it Martial/Forest Law that you typically picked while playing?

Momoda: Yeah, Forest Law and Paul Phoenix were who I liked at first. In Tekken 2 I liked Lei Wulong, because he was a Jackie Chan-style character and I liked all those springy kicks and piston-like punches. I’m disappointed he’s no longer in the game.

Time Extension: Your dislike of the name "Tekken" is something that you also brought up in your "Making Of". Could you expand on why you didn’t like the name? Do you remember any of the alternative names that were floating around?

Momoda: Tekken had zero meaning to English-speaking people. And in my job, I was trying to make games more relevant to American players. At that time, raves and rave parties were popular. So I suggested Rave War. We kind of went around on a few other ideas, but in retrospect, I’m glad that they stayed with Tekken. Had the game not succeeded, some may have said it was due to the name.

Time Extension: Yeah, there were a lot of fighting games around the time that had these kinds of really generic. The Simpsons kind of made fun of it with a fake fighting game that they created called Bonestorm, which was sort of Mortal Kombat-ish. But yeah, a lot of the names were like “Blood” or “Bone” and then something else. It was these really extreme names that were probably cool in the ‘90s, but haven’t necessarily aged well. I feel like Tekken is the perfect name for the fighting series, potentially because most people don’t know what it means.

Momoda: Had you been in the moment, you may have thought differently. Hindsight’s 20/20. You mentioned “Blood” and The Simpson’s “Bonestorm”. At Atari, I was constantly encouraging engineering to make a fighting game that could compete with the likes of Street Fighter, Virtua Fighter, and Mortal Kombat. So much so that they nicknamed me “Blood & Guts Momoda” (laughs).

Finally, one team agreed to make a fighting game. But the team prioritized digitized graphics (a la Mortal Kombat) over core gameplay. And despite my advice against it, the designer just wanted to make a casual button-masher. After lukewarm success, the team was not deterred. Instead, they chose to make a second button masher. These games weren’t skill-based and their time had come and gone. You can imagine my excitement, then, when I got the offer from Namco. They desperately wanted to succeed in North America and were leaps ahead in 3D technology.

In coin-op, I worked for four Japanese and one American company. I found it ironic that my input at Japanese companies was more valued and effective than at Atari. I attribute that in part to how the Japanese value the group and how at Atari it was more about the individual.

Time Extension: I'm wondering, do you have any memories of the original Tekken’s promotional tour? I remember reading that there was a tour around the country or the States to promote the game ahead of its release.

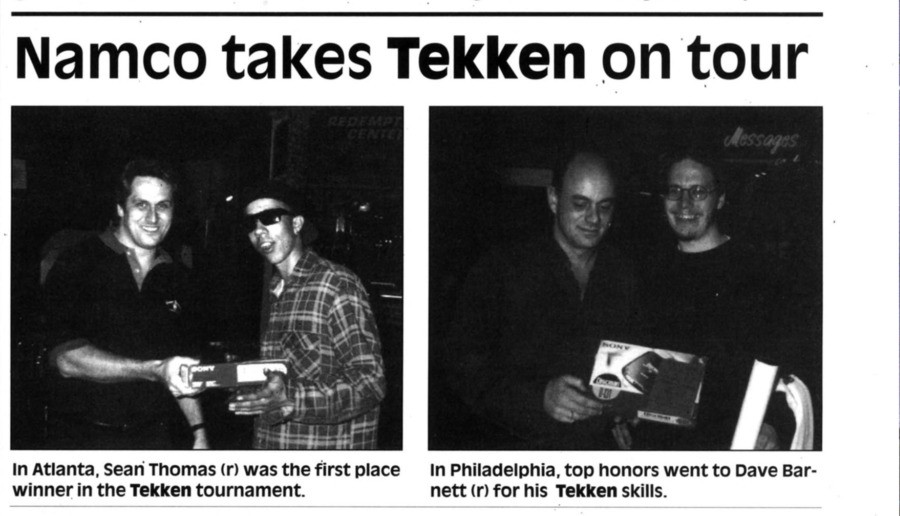

Momoda: Yeah, it was a little North American tour – just a promotional thing. For each big title, we’d go to distributors and have “spotlight shows”. As a product manager, I would accompany the sales team to demonstrate gameplay, answer questions, and help drive sales. We sent games to key distributors and arcades around the US & Canada to create excitement and hype for our test results. In coin-op, earnings are the measuring stick to compare games. And for our distributors and their operator customers, earnings in their own locations were more believable than those provided by Namco. I was confident in the game after our local testing. So much so that I felt comfortable placing the game in any location.

Time Extension: When did you start believing that the game was going to be something special and potentially have legs?

Momoda: Very early. My intuition told me the game was good. The game had great initial appeal and reaction. The skill element provided the depth to keep players immersed over time. And fighting games have short playtimes. Players love competition. The constant player turnover provided a constant flow of quarters going into the game. It’s rare that you can identify a clear winner, but Tekken was one of those. I loved the game but tried to reserve judgement because I was too close to the project. And though I worked on it every day, I still had to pay attention to earnings because, in the end, that’s all that mattered.

I worked in games at the time when little data was available. I could tell if players liked a game by looking in the cashbox, but that data wouldn’t tell of issues or how to solve them. Years before, I was recruited to work for Nintendo after the VP of Marketing watched me play Donkey Kong at a bar. He asked me questions and appreciated how I could dissect the game. The full story is on my website, jerrymomoda.com. My jobs at Nintendo, Sega, SNK, and Atari taught me a lot.

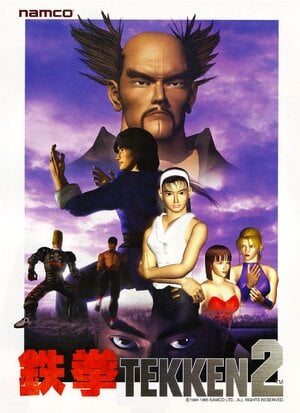

Time Extension: Tekken 2 obviously followed very shortly after the first game. Do you have any good memories from working on that game? Or any favourite features that were added or any favourite characters?

Momoda: I made an important contribution to Tekken 2. That was shaping the time-release feature in the game.

For some background, in the arcade world at that time, if you wanted to introduce new characters to a game like Midway’s Mortal Kombat, the game had to be turned off, chips pulled, and taken to their distributor to be updated. That resulted in crucial downtime because the game was not in operation. A game that is down is not making any money for the operator.

In the early days of Tekken 2 development, my counterpart in Japan, Kohei Teraoka informed me of an internal time clock that could be used to release new characters. The team recommended introducing each new character one-by-one, simultaneously around the world. So let’s say, on June 1st, character X would pop no matter where in the world the game is. I thought that was an amazing feature because the game wouldn’t have to be manually updated. And due to this internal time clock, it would happen automatically. With no downtime to interfere. But then I thought of a better idea that had the potential to drive sales.

I suggested to the team a method where new characters would be released according to how long the game was up and running on location. That meant if a new character would be introduced after say 50 hours of operation, only those games having at least 50 hours in operation would get the released character. Therefore, the operator who operated Tekken first in his neighborhood would be the first to get the new character. Players talk to each other and would know which location had more characters. That location would benefit from it. The result is it incentivized operators to buy games early rather than wait as many operators traditionally did. Why is this important for a manufacturer? In the old world of arcade games, physical parts and manufacturing dealt with the ordering of parts, lead times, and shipping. Naturally, it’s better to know the demand for your product as soon as possible. Having to guess can be risky. In a nutshell, it’s way more efficient.

After Tekken 1’s introduction, we soon started working on a sequel. What could we do to expand the popularity of the game? We needed to build a brand to tell a story so that players felt invested in what I hoped would become a series. Namco Japan wrote the story. I thought it was odd and I asked a few in my office for suggestions. Unsurprisingly, our story changes were rejected. Since I was wrong with the game name, I didn’t object too much to the story. In hindsight, I should have (laughs).

Time Extension: This is not Tekken-related, but I have to bring up Soul Blade or Soul Edge, which came out shortly after Tekken 2. Do you remember your experiences of seeing that for the first time?

Momoda: It kind of caught me by surprise. When I saw an early prototype, I thought it made sense as a natural derivative. But why at the same time? In the arcade market, it somewhat cannibalized sales because they were both fighting games. But each game had a strong following and their combined sales proved it beneficial.

Time Extension: Do you remember any kinds of conversations when Soul Blade came in in terms of how you were going to market these two at roughly the same time?

Momoda: Well, you know, I guess the proof in the pudding was if you put it out on location with a Tekken game. They each had their own separate camp of fans. But in the long run, Soul Calibur didn’t have the legs that Tekken had. I think there’s so much more you can do with a hand-to-hand fighting game than swords.

Time Extension: It’s fascinating you mention about the hand-to-hand thing and it having more opportunities. What Tekken obviously excelled at was introducing these new sort of fighting techniques, whereas I guess with a sword, there are only so many ways you can swing it.

Momoda: Yeah, how do you defeat an opponent while sword fighting without it ending in a gory death? Think of any good samurai movie. But I’m glad the team didn’t make it gory, especially given the criticism of gratuitous violence in games. Part of the appeal of a fighting game is the visual reward after a successful attack. When that’s not there, you lose some of the immersion factor.

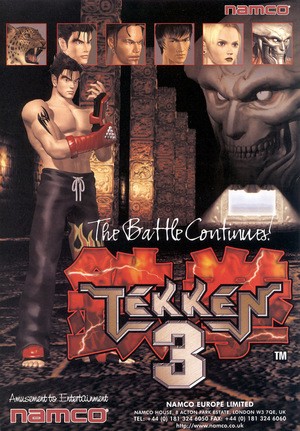

Time Extension: In terms of Tekken 3, it’s amazing to see the advancement in technology with the introduction of the System 12 board and the evolution of the graphics in both the arcade and the console versions as well. Were there any teething problems as part of that evolution? What do you remember about that?

Momoda: For developers, there usually aren’t “teething problems” when given more capacity and performance. Perhaps in optimization, but that’s another story. In Tekken 3, I felt the game blossom and come to life as graphics were richer and fighting became more detailed. Of all the Tekken games, Tekken 3 is my favourite because it really made a quantum leap. The look and feel took a step forward. A lot of long-time fans of the series recognize Tekken 3 as their favorite as well.

After Tekken 3, I was sent some Tekken soundtrack CDs. The music was and is still amazing. I still listen to them.

Time Extension: Do you have any favourite features that were added with Tekken 3? It was amazing to see characters like Eddy Gordo being introduced and those different types of fighting techniques still being incorporated into the games.

Momoda: I think the 3D sidestepping function really demonstrated the 3D ability of the game. But since its displayed on a two-dimensional screen, you’re still fighting in two-dimensions.

And yes, Eddy Gordo was good for the game. His fighting style, Capoeira, was refreshing and contributed greatly to the game.

Time Extension: We have to ask, how much did Namco US grow over the course of those three games? Was it significantly larger by the time that it got to Tekken 3?

Momoda: The coin-op side in San Jose never staffed up that much. We did add some manufacturing-related staff who were needed to procure parts stateside. Probably the side that grew the most was Hometek – the consumer side – because their business was really taking off. And Hometek started their own internal development of games for consoles. Early on they had a lot growing pains.

Time Extension: This is another question that's not necessarily Tekken-related. You mentioned location tests earlier on, were there any Namco games that you brought over from Japan and put on location in the States that didn’t do well? Or was it usually a hit whenever you put something out there?

Momoda: There were several games that we would pass on because either they were Asian market-specific or didn’t test well.

In the US, only certain genres were successful. Some games had very niche audiences or their earnings weren’t enough to support importing them. For games to earn a lot of quarters, they need short playtimes and constantly be in play. There’s not a lot of games that can do that. Over the years, we tested a lot of games just because Namco Japan wanted us to. Remember, back in the days before the PlayStation, players had to leave home and spend coins/cash to play a game. They were the more frequent, hardcore players. The niche casual games of today would not have [warranted] investing the time and money.

Time Extension: Were there any games you remember that did surprisingly well that you didn’t think would succeed?

Momoda: Point Blank was a casual player's gun game that did surprisingly well.

Time Extension: You left Namco in 1998. When was the decision made to leave? And what have you been up to since?

Momoda: By Tekken 3, the PlayStation was hugely successful. But I saw coin-ops impending doom soon after the first Tekken. Namco partnered with Sony in the development of System 11. Without Sony, System 11 would not have been as good. And without Namco, the PlayStation would not have been adopted as fast by players. Several Namco coin-op games became PS launch titles. Arcades were the proving ground. But consoles were where the really big money was made. This symbiotic relationship proved to be a double-edged sword for Namco. While Namco produced successful coin-op games on this hardware, it proved arcade-quality games would be available for the home. For years, the best hardware and best games were clearly at the arcade. The Sega and Nintendo home systems could not compete with constantly evolving arcade hardware. Once I saw the PlayStation was the equal to System 11, I knew coin-ops long reign was over.

And so, the only card we could play was to create game experiences that couldn’t be duplicated at home. I provided concepts for games that were more location-based. During the time of early Tekken, I provided a concept that lent itself to what eventually became Time Crisis. Our location-based games had special controls and cabinet configurations with seats that could only be played in the arcade.

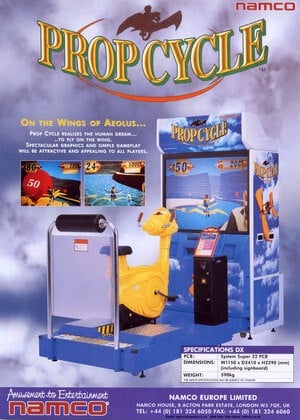

One such game was called Prop Cycle. Players controlled a turn-of-the-century, self-propelled glider by pedalling. It was so unique. I’m still disappointed that more wasn’t done with a game like that. It was very creative and way ahead of its time. Exercise could add to a player’s sense of moment-to-moment action, but game players aren’t necessarily athletes. We also developed two snow-based games, Alpine Racer (skiing) and Alpine Surfer (snowboarding) that were successful. Tokyo Wars, Speed Racer, Final Furlong, and Rapid River were less so.

Business in the arcade world continued falling off and I was a victim of the downturn. I remember the Tekken team being shocked that something like that could happen because I was important to the Tekken project. It was Namco’s most successful franchise. But, you know, that’s the way of the world. That’s business. I’m proud that with Tekken 1, 2, and 3, company revenues doubled for three consecutive years and unit sales volume grew eight-fold over four years. I’m not sure if it still holds true, but not long ago Tekken was the most successful fighting game in history.

Today I’m retired. I have hobbies and sports I enjoy. I’m snow skiing again and play golf. I still game, have a Nintendo Switch, PS5, and a sim-racing rig. I’ve enjoyed the Legend of Zelda games of late.

Time Extension: That’s a shame.

Momoda: I worked at other game companies but nothing could ever rival the fun of my early career. From my first job at Nintendo, I never would have predicted I’d have the career I had in gaming. I was very fortunate.

Time Extension: When is the last time that you’ve played on a real Tekken cabinet?

Momoda: It’s been a long time. It’s been a long time! I don’t even have Tekken 8.

Time Extension: Namco should probably just send you a copy out of courtesy.

Momoda: I agree. I agree (laughs). But I think most people don’t even know that I worked on the first Tekken or was instrumental in shaping the franchise. Thank you for this opportunity to share my experiences.

Time Extension: Thank you for your time, Jerry! Namco, you know what to do!